Shingles – Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention

When dealing with shingles, a painful skin rash caused by reactivation of a dormant virus. Also known as herpes zoster, it typically appears as a band of blisters on one side of the body. Varicella‑zoster virus, the same virus that gives you chickenpox in childhood lies low in nerve tissue until something weakens your immune system. Once reawakened, the virus travels along nerve fibers, causing the classic rash and burning sensation. This chain of events shows how shingles encompasses viral latency, nerve involvement, and skin eruption.

The Varicella‑zoster virus, a DNA virus from the herpes family, prefers to hide in dorsal root ganglia after the initial chickenpox infection. When immunity drops—due to age, stress, or medication—the virus can reactivate, leading to shingles. Understanding this trigger helps explain why older adults or immunocompromised patients are at higher risk. The virus’s ability to travel along sensory nerves also explains why the rash follows a dermatomal pattern rather than spreading randomly across the skin.

Stopping the virus early hinges on antiviral therapy, medications that inhibit viral DNA replication, most commonly acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. These drugs work best when started within 72 hours of rash onset, reducing lesion duration and the chance of complications. Dosage varies by age and kidney function, but the goal is consistent blood levels to keep the virus from multiplying. Prompt antiviral use also lowers the risk of developing chronic pain after the rash clears.

Prevention starts with vaccination. The shingles vaccine, a recombinant subunit vaccine that boosts VZV‑specific immunity (commercially known as Shingrix) is recommended for adults 50 years and older, even if they’ve had shingles before. A two‑dose schedule spaced two to six months apart provides over 90 % protection against both shingles and its most dreaded sequel, postherpetic neuralgia. For those who cannot receive Shingrix, the older live‑attenuated vaccine (Zostavax) remains an option, though its effectiveness wanes faster.

One of the biggest worries after an outbreak is postherpetic neuralgia, persistent nerve pain lasting months or years after the rash resolves. This pain arises from nerve damage inflicted during viral reactivation. Management often requires a mix of medications: gabapentin or pregabalin for neuropathic pain, topical lidocaine patches, and sometimes low‑dose tricyclic antidepressants. Early use of antiviral therapy reduces the likelihood of this chronic pain, but when it does occur, a multimodal approach is essential for quality of life.

Beyond drugs and vaccines, lifestyle factors matter. Maintaining a healthy diet, staying active, and managing stress support immune function, lowering the chances of VZV reactivation. For people on immunosuppressive therapy—organ transplant recipients, chemotherapy patients, or those with HIV—regular discussions with a healthcare provider about timing of vaccination and prophylactic antivirals are crucial. Understanding the full picture—from the virus itself to treatment options, preventive shots, and pain‑management strategies—empowers anyone facing shingles to act quickly and prevent long‑term complications.

Below you’ll find a curated selection of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics, offering practical tips, drug comparisons, and up‑to‑date guidance to help you manage or prevent shingles effectively.

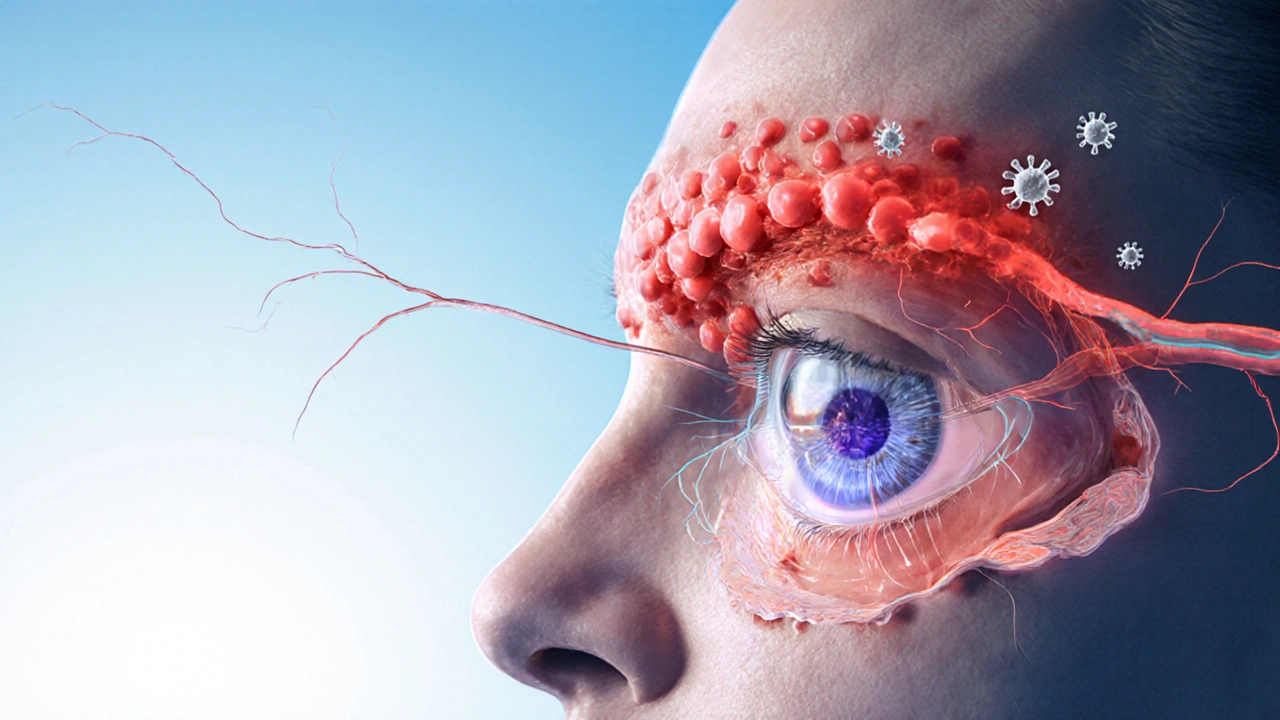

Protect Your Vision from Shingles: Eye Risks and Prevention Tips

16 Comments

Learn how shingles can affect your eyes, spot early warning signs, and use vaccines and prompt treatment to safeguard your vision.

Read More