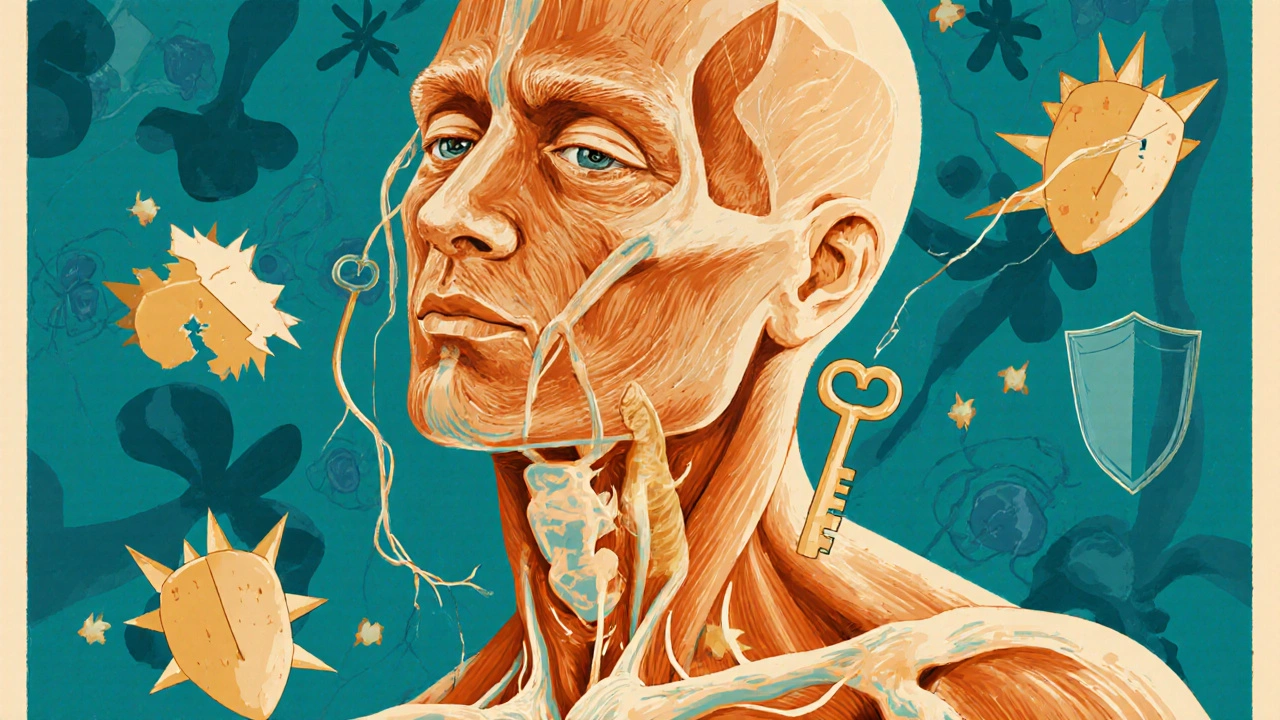

Myasthenia gravis isn't just muscle weakness. It’s weakness that gets worse when you use your muscles-and gets better when you rest. Imagine lifting your eyelids, only to have them droop halfway through the day. Or struggling to chew your food, then suddenly being able to swallow again after a nap. That’s the hallmark of myasthenia gravis (MG): fatigable weakness. It doesn’t stay constant. It comes and goes, flares up with activity, and fades with rest. This isn’t laziness or aging. It’s your immune system mistakenly attacking the connection between your nerves and muscles.

What Causes the Weakness?

Your muscles don’t move on their own. They need a signal from your nerves. That signal is sent using a chemical called acetylcholine. At the junction where nerve meets muscle, acetylcholine binds to receptors-like a key turning in a lock-to make the muscle contract. In myasthenia gravis, your body makes antibodies that block or destroy those receptors. Without enough working receptors, the signal gets lost. The muscle doesn’t respond. That’s the weakness.

Eighty to ninety percent of people with generalized MG have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). A smaller group-5 to 8%-have antibodies against something called MuSK. The rest are seronegative, meaning no known antibodies are found, but the disease still behaves the same. This isn’t random. These antibodies are the direct cause. They’re not just a marker-they’re the enemy.

It often starts in the eyes. About 85% of people first notice drooping eyelids (ptosis) or double vision (diplopia). For some, it stays there. But for half to 80% of those with only eye symptoms, it spreads to other muscles within two years. That’s called generalized MG. Then you might have trouble speaking clearly, swallowing, lifting your arms, or climbing stairs. The weakness is most noticeable after activity and improves after rest. That’s why it’s called fatigable.

Who Gets It and Why?

Myasthenia gravis can strike at any age, but it has two clear peaks. People under 50-especially women-are more likely to develop early-onset MG. In these cases, the thymus gland (a small organ in the chest that helps train immune cells) is often enlarged and overactive. The thymus is thought to be where the bad antibodies are first made.

People over 50, especially men, tend to develop late-onset MG. Here, the thymus is often shrunken, but about 10 to 15% have a thymoma-a benign tumor. That tumor can trigger the same autoimmune response. The reason why the immune system turns on itself isn’t fully known. Genetics may play a role, but environmental triggers like infections or stress are likely involved too.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t just guess. They use tests that show the nerve-muscle connection is broken. The most common is the edrophonium test-a quick injection that temporarily boosts acetylcholine. If your eyelids lift or your speech clears within seconds, it’s a strong sign of MG.

Blood tests look for AChR or MuSK antibodies. These confirm the diagnosis in most cases. But even if antibodies are negative, the disease can still be there. That’s when doctors use nerve conduction studies, especially repetitive nerve stimulation. In MG, the muscle response gets weaker with repeated stimulation-something that doesn’t happen in healthy nerves.

They also use the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis Score (QMGS). It’s a checklist of 15 tasks: lifting arms, walking up stairs, speaking, swallowing. Each gets a score. A total over 11 means moderate to severe disease. That tells doctors when it’s time to move beyond symptom relief and start immunotherapy.

First-Line Treatment: Symptomatic Relief

Before attacking the immune system, doctors often start with pyridostigmine. This drug slows down the breakdown of acetylcholine, so more of it hangs around to bind to the remaining receptors. It’s not a cure. It’s a bridge. People take 60 to 240 mg a day, split into doses. It helps with eyelid drooping, speech, and swallowing-but it doesn’t stop the immune attack. It just buys time.

Side effects? Nausea, cramps, increased saliva. But it’s usually well-tolerated. Many people live for years on pyridostigmine alone, especially if their disease is mild or stays in the eyes.

Immunotherapy: Turning Off the Attack

Once the disease spreads beyond the eyes, or symptoms get worse, it’s time for immunotherapy. This isn’t about fixing the muscle. It’s about stopping your immune system from destroying it.

Corticosteroids like prednisone are the most common first-line immunosuppressant. They’re powerful. About 70 to 80% of patients see major improvement or even complete remission. But they come with a cost. Weight gain, mood swings, bone thinning, high blood sugar. Many people gain 10 to 20 pounds within months. Long-term use isn’t sustainable.

That’s why doctors add steroid-sparing agents as soon as possible. Azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are the two main ones. Azathioprine takes 6 to 18 months to work fully, but once it does, about 60 to 70% of patients can reduce or stop steroids. Mycophenolate works faster-often within 3 to 6 months-and has fewer liver side effects. About half to 60% respond well.

But here’s the catch: not all types of MG respond the same.

Subtype Matters: AChR vs. MuSK

MG isn’t one disease. It’s two or three different ones, depending on the antibody. That changes treatment.

AChR-positive MG responds well to standard immunosuppressants. But MuSK-positive MG? It’s different. These patients often have severe bulbar weakness-trouble speaking and swallowing-and don’t respond as well to pyridostigmine or azathioprine. For them, rituximab is a game-changer. It targets B-cells-the immune cells that make the bad antibodies. Studies show 71 to 89% of MuSK-positive patients reach minimal symptom status with rituximab, compared to just 40 to 50% of AChR-positive patients.

That’s why testing for antibody type isn’t optional. It’s essential. Giving the wrong drug can waste months and let symptoms worsen.

Fast-Acting Options for Crises

What if someone can’t swallow, can’t breathe, or is about to be rushed to the ICU? That’s a myasthenic crisis. You need fast action.

Two treatments work quickly: intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and plasma exchange (PLEX). Both clear out the bad antibodies-but differently.

IVIG gives you healthy antibodies from donors. These flood your system and confuse your immune system into stopping the attack. It takes 5 to 7 days to work, and the effect lasts 3 to 6 weeks. It’s easier to give-just an IV drip-but it’s expensive and can cause headaches or fever.

PLEX literally pulls your blood out, removes the plasma (where the bad antibodies live), and returns your blood cells with fresh plasma. It works faster-2 to 3 days-and is often preferred in life-threatening cases like respiratory failure. But it needs a central line, carries infection risks, and isn’t available everywhere.

Both are equally effective in trials. The choice comes down to speed, availability, and patient condition.

Thymectomy: Removing the Source

If you’re under 65, have AChR-positive MG, and have a thymus that’s enlarged or abnormal, surgery to remove it-thymectomy-is recommended. The MGTX trial showed that patients who had thymectomy plus steroids reached remission faster than those on steroids alone. After five years, 35 to 45% of early-onset patients were in complete remission without any drugs.

It’s not a magic fix. But for the right person, it’s the best shot at long-term freedom from meds.

New Frontiers: Targeted Immunotherapies

The last five years have changed everything. New drugs don’t just suppress the whole immune system. They target specific parts of the problem.

Efgartigimod blocks the FcRn receptor-the body’s recycling system for antibodies. Normally, your body saves IgG antibodies (including the bad ones) and reuses them. Efgartigimod tells the body to destroy them instead. In the ADAPT trial, 68% of patients reached minimal manifestation status within weeks. It’s given weekly by IV, and the FDA approved it in 2021.

Then came ravulizumab, a complement inhibitor approved in 2023. It stops a specific part of the immune system from attacking the muscle membrane. It’s given every 8 weeks by IV.

These drugs are faster, more precise, and have fewer side effects than steroids or azathioprine. But they’re expensive. And long-term data beyond two years is still limited.

The Dark Side: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

There’s a dangerous twist. Cancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are designed to wake up the immune system to fight tumors. But in about 60% of cases, they accidentally trigger or worsen MG. These cases are often severe-60% involve heart inflammation (myocarditis), and 83% need ICU care. Doctors now warn: if someone on these drugs suddenly gets weakness, think MG. It’s a medical emergency.

Living With MG: Long-Term Realities

Most people with MG need long-term treatment. About 85 to 90% stay on some form of immunosuppression. But that doesn’t mean a life of constant struggle. With the right treatment, most reach “minimal manifestation status”-meaning symptoms are so mild they barely notice them.

Thymectomy, early treatment, and choosing the right immunotherapy can lead to remission. Younger patients have the best shot. About 10 to 20% go into spontaneous remission without any treatment-but that’s rare and unpredictable.

The biggest challenge? Tapering drugs too soon. If you stop immunosuppressants before you’ve been symptom-free for at least two years, you have a 40 to 50% chance of relapse. Patience is key.

Side effects are real. Weight gain from steroids. Liver damage from azathioprine. Infections are 2 to 3 times more common when you’re on multiple immunosuppressants. Vaccines are critical. Avoid live vaccines. Stay up to date on flu, pneumonia, and shingles shots.

What’s Next?

The future is targeted. New drugs are in trials: rozanolixizumab (subcutaneous, weekly), inebilizumab (B-cell targeting), and more FcRn blockers. The goal? Not just control-but cure. Researchers want to eliminate the bad antibodies without shutting down the whole immune system.

Right now, the best outcomes come from matching the treatment to the subtype, acting early, and avoiding unnecessary steroids. Myasthenia gravis isn’t a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition that can be managed-with the right science, the right drugs, and the right plan.

Comments

Sameer Tawde November 17, 2025 at 21:33

Been living with MG for 7 years. Pyridostigmine got me through my first year. Now on mycophenolate and barely notice the drooping. It’s not perfect, but I can hold my coffee without spilling it. That’s a win.

Rest is your best friend. No guilt in napping after lunch. Your body’s not lazy-it’s fighting.

Jeff Hakojarvi November 19, 2025 at 17:14

just wanna say thank you for writing this so clearly. i’ve been trying to explain mg to my family for months and this is the first time i felt like they actually got it. the part about fatigable weakness? yes. that’s it exactly. not tired. just… gone. like a battery that drains when you use it.

also, ivig is a lifesaver. i had my first one last month and could swallow again after 3 days. i cried. not because it cured me, but because i remembered what it felt like to eat without fear.

Timothy Uchechukwu November 20, 2025 at 04:25

so you’re telling me some rich white people got a disease because their immune system is too weak to handle a few viruses and now we’re spending millions on drugs that don’t even cure it?

why not just tell them to stop being so delicate and eat more vegetables. i mean look at africa we don’t have these fancy meds and we still walk. maybe mg is just a symptom of modern laziness.

Ancel Fortuin November 22, 2025 at 04:16

oh sure. let’s blame the thymus. next they’ll say the moon is made of cheese and that’s why your eyelids droop.

they don’t want you to know the real cause: 5G towers, glyphosate in your oat milk, and the CDC hiding the truth because they’re paid by big pharma to keep you hooked on $20,000/month infusions.

you think that ‘new drug’ is science? nah. it’s a money laundering scheme with a stethoscope.

and don’t even get me started on thymectomy. they cut out your thymus and then wonder why you get sick again. genius move, doctors. real genius.

Hannah Blower November 22, 2025 at 23:22

It’s fascinating how the medical establishment has reduced an autoimmune phenomenon-deeply entangled with neuroimmunological identity-to a checklist of antibody titers and QMGS scores.

There’s an existential weight here: the body as a broken machine, the self as a malfunctioning receptor. We’ve pathologized vulnerability. We call it ‘fatigable weakness’ when what we’re really seeing is the soul’s exhaustion from being forced to perform normalcy.

And yet, we treat it like a software bug. Patch it with rituximab. Reboot with IVIG. But who’s debugging the trauma of living in a body that betrays you daily?

It’s not a disease. It’s a metaphysical glitch in the human operating system.

Gregory Gonzalez November 23, 2025 at 03:41

Of course the article mentions ‘minimal manifestation status’ like it’s some kind of victory lap. Newsflash: if you need to take a drug that costs more than your car just to hold up your head, you’re not ‘minimally manifesting’-you’re surviving on a technicality.

And don’t get me started on ‘remission.’ That’s just a fancy word for ‘we stopped giving you steroids because you stopped looking like a patient.’

Real talk: MG doesn’t go away. It just learns to hide. And so do you.

Ronald Stenger November 23, 2025 at 15:08

Why are we letting pharmaceutical companies dictate treatment? They invented the term ‘seronegative’ to sell more tests. They pushed rituximab for MuSK because it’s profitable, not because it’s better.

And now we’re paying $100K/year for drugs that were developed with NIH funding? That’s not science. That’s corporate theft wrapped in a lab coat.

Meanwhile, people in developing countries are dying because they can’t afford a single infusion. This isn’t medicine. It’s a luxury market disguised as healthcare.

Samkelo Bodwana November 24, 2025 at 22:59

I’ve read this whole thing twice. And I still feel like I need to sit with it. MG isn’t just a diagnosis-it’s a whole new way of moving through the world. You learn to measure your life in energy units instead of hours. You start saying no to things you used to love because your body says no before your mind even asks.

But here’s what no one talks about: the quiet resilience. The way someone with MG learns to find joy in the small things-like the first sip of tea without choking, or the ability to laugh without fearing a breath that won’t come.

I’ve met people with MG who’ve run marathons, raised kids, taught classes. They don’t fight the disease. They dance with it. And that’s the real medicine.

It’s not about curing. It’s about living with the rhythm of your own body, even when it’s out of sync.

And maybe that’s the lesson for all of us.

Everyone’s weak somewhere. MG just makes it visible.

Duncan Prowel November 25, 2025 at 09:47

While the article provides a clinically accurate overview, it omits a critical nuance: the psychosocial burden of chronic autoimmune disease in the context of Western healthcare systems. The pressure to achieve ‘minimal manifestation status’ as a metric of success imposes a performative expectation upon patients, wherein their subjective experience of illness is subordinated to quantifiable benchmarks.

Furthermore, the emphasis on antibody subtyping, while scientifically valid, inadvertently reinforces a reductionist paradigm that may overlook the heterogeneity of patient response. For instance, the phenomenon of seronegative MG, despite lacking identifiable autoantibodies, exhibits identical clinical trajectories-suggesting that our current immunological taxonomy may be incomplete.

One might also question the ethical implications of deploying ultra-expensive biologics in resource-constrained settings, where access to basic neurology care remains uneven. The disparity in therapeutic access is not merely economic-it is epistemic.

Future research must prioritize patient-reported outcomes over biomarker-centric endpoints, and decentralize care models to mitigate systemic inequities.

Bruce Bain November 25, 2025 at 10:57

Man, I didn’t know MG was this complicated. I thought it was just tired muscles. But reading this… it’s like your body’s got a traitor inside. And the doctors are trying to find the traitor and stop them.

My cousin’s got it. She used to dance. Now she can’t lift her phone. But she still smiles. I didn’t know what to say till I read this. Thanks.

Also, if anyone’s got a good doctor in Texas, hit me up. She needs help.

benedict nwokedi November 26, 2025 at 06:49

Let’s be real: the entire ‘MG treatment protocol’ is a controlled demolition of patient autonomy. They test you for antibodies, then they lock you into a drug pipeline based on what the FDA approved last quarter-not what actually works for YOU.

And the ‘new frontier’ drugs? Efgartigimod? Ravulizumab? These aren’t breakthroughs-they’re patent extensions disguised as innovation. The real breakthrough would be a cure. Not a $100,000/month subscription.

Meanwhile, the thymus? They cut it out like it’s a tumor. But they never ask: why was it even making bad antibodies in the first place? Was it the vaccines? The mold? The EMF? The answer’s buried under 12 layers of corporate-funded research.

And don’t get me started on ‘spontaneous remission.’ That’s just the immune system getting bored of attacking you. Maybe it’s on vacation.

deepak kumar November 27, 2025 at 10:30

As someone from India who’s seen MG in rural clinics, I can say: most patients never get tested for MuSK or AChR. They just get steroids and hope. No IVIG, no rituximab, no thymectomy.

But you know what? Many still find ways to live. They rest when they need to. They eat lentils. They sit in the shade. They don’t have fancy scores, but they have family. And that’s a kind of therapy too.

Also, pyridostigmine is available here for under $5 a month. We don’t need $20K drugs to survive. We need access.

Science is great. But humanity? That’s what keeps people walking.

Dave Pritchard November 29, 2025 at 01:14

My sister was diagnosed last year. She’s 29. She cried for three days straight. I didn’t know what to say. Then I started reading everything I could find. This post? It’s the first thing that made me feel like I actually understand.

You’re not alone. Even when your body feels like it’s turning against you, people are out here learning, listening, trying to help.

And if you’re reading this and you have MG? You’re already winning. Just by showing up. Every day. Even if you had to rest halfway through.

kim pu November 30, 2025 at 08:19

Okay but imagine if your muscles were just… out to lunch? Like, they got a union, voted to strike, and now they’re like ‘nope, we’re not lifting that cup unless you give us a nap and a latte’.

That’s MG. Not a disease. A passive-aggressive rebellion by your own body. And the doctors are like ‘here’s a $20k coffee machine to fix it’.

Also, why is rituximab the MVP for MuSK? Because B-cells are the drama queens of the immune system. They show up, throw a party, and then leave you with a hangover.

And don’t even get me started on ‘minimal manifestation status’-that’s just doctor-speak for ‘you’re not crying in public today’.

malik recoba December 1, 2025 at 01:06

i’ve had mg for 10 years. started with just droopy eyes. now i’m on mycophenolate and it’s a game changer. i can hold my kid again. i can walk to the mailbox without stopping.

the meds ain’t perfect. i get tired. i get scared. but i’m here. and i’m not giving up.

if you’re new to this? breathe. you’re gonna be okay. not perfect. not cured. but okay.

and if you’re reading this and you’re a doc? thank you. you’re doing better than you think.

Sameer Tawde December 2, 2025 at 04:00

Sameer here. Just read the comment about rituximab and MuSK. That’s spot on. My cousin has MuSK-positive. She tried azathioprine for a year. Nothing. Then rituximab-boom. In 6 weeks, she could speak clearly again. That’s the difference between guessing and knowing.

Test the antibodies. Don’t guess. It matters.