When someone takes too many drugs at once - say, opioids, painkillers, and benzodiazepines - it’s not just a bad day. It’s a medical emergency that can kill in minutes. Multiple drug overdose is one of the most dangerous scenarios in emergency medicine, and it’s getting worse. In 2019, over 120,000 people worldwide died from opioid overdoses alone. Add in acetaminophen, alcohol, or benzodiazepines, and the risk multiplies. The body doesn’t handle these combinations well. One drug masks the symptoms of another. One antidote might undo the work of another. Getting it right means knowing exactly what to do - and when.

What Makes Multiple Drug Overdose So Dangerous?

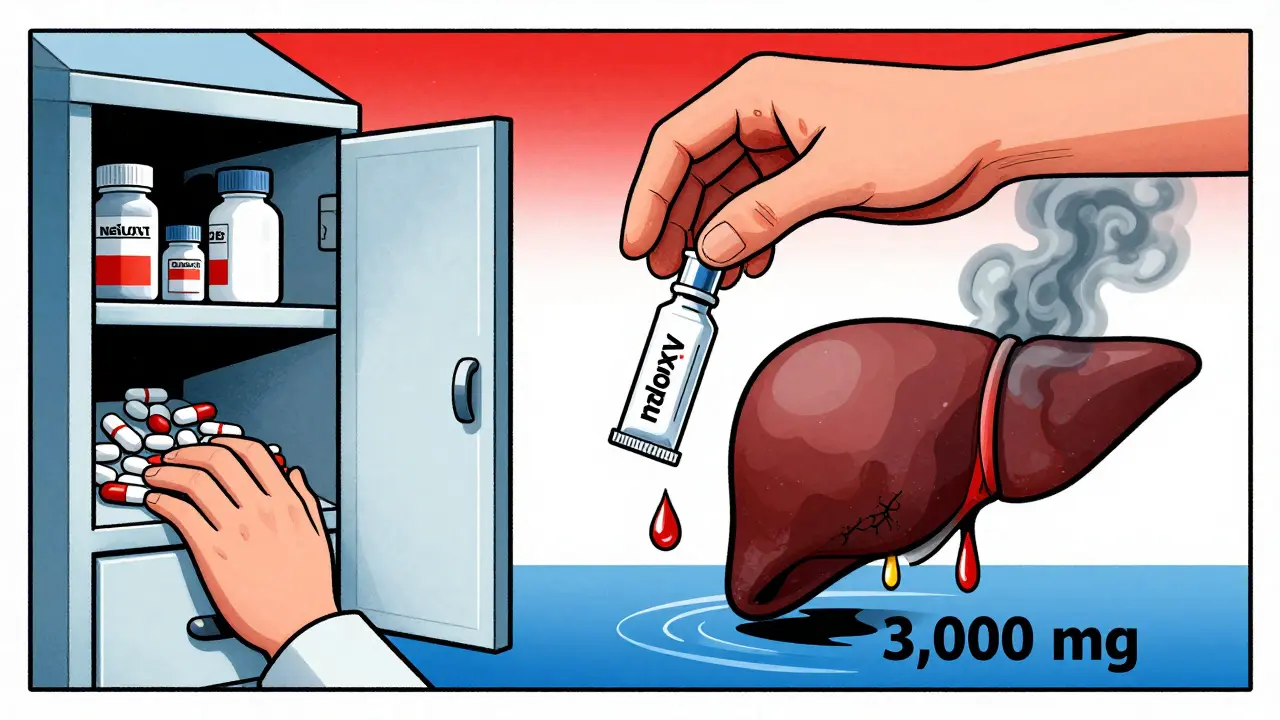

It’s not just the amount of drugs. It’s the mix. Take a common prescription combo like Vicodin or Percocet - they contain both an opioid (hydrocodone or oxycodone) and acetaminophen. Take too many, and you’re risking two life-threatening problems at once: respiratory failure from the opioid and liver failure from the acetaminophen. These don’t happen one after the other. They happen together.

And it gets worse. Fentanyl is now the biggest killer in opioid overdoses. It’s 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin. A tiny amount can stop breathing. But if the person also took Xanax or sleeping pills, the sedation gets worse. The brain stops telling the lungs to breathe. And naloxone, the opioid reversal drug, might not work fast enough - or might wear off before the fentanyl leaves the system.

Then there’s acetaminophen. It’s in over 600 medications. People don’t think of it as dangerous. But take more than 10 grams in a day - or just a few extra pills over several days - and your liver starts dying. The problem? You might feel fine for hours. No vomiting. No pain. Just quiet, invisible damage. By the time you feel sick, it’s often too late.

First Responders: The Five Essential Steps

If you’re the first person on the scene, you have minutes to act. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has clear, proven steps:

- Assess the situation. Is the person responsive? Are they breathing? Are their lips blue? Are there pill bottles nearby? Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse.

- Call emergency services. Even if you give naloxone, they still need a hospital. Overdose recovery isn’t instant.

- Administer naloxone. If you suspect opioids - even just one - give naloxone. Use the nasal spray. Spray one dose into one nostril. If there’s no response in 2-3 minutes, give a second dose. For fentanyl overdoses, you might need three or more.

- Support breathing. If they’re not breathing or breathing shallowly, start rescue breathing. One breath every 5 seconds. Don’t wait for naloxone to kick in. Oxygen is life.

- Monitor closely. Naloxone wears off in 30-90 minutes. Fentanyl and other long-acting opioids can stay in the body for hours. The person can stop breathing again. Stay with them until EMS arrives.

Don’t wait for the ambulance to start breathing for them. Rescue breathing alone can save a life - even without naloxone.

Hospital Protocol: Juggling Antidotes

In the ER, things get more complex. Doctors aren’t just treating one poison. They’re managing a chemical war inside the body.

For acetaminophen overdose, the key is acetylcysteine. But timing matters. If the person took the pills less than 4 hours ago, activated charcoal might still help - it binds the drug in the gut before it enters the bloodstream. But if it’s been more than 4 hours, acetylcysteine is the only thing that works. The old Rumack-Matthew nomogram is still used, but it’s been updated. Now, doctors look at blood levels and liver enzymes. If the acetaminophen level is above 20 μg/mL, or if AST/ALT (liver enzymes) are rising, they start acetylcysteine - even if the person doesn’t look sick.

Here’s the tricky part: you give naloxone for the opioid. You give acetylcysteine for the acetaminophen. But naloxone lasts less time than acetylcysteine. So the person might wake up - breathing fine - and then crash again 2 hours later when the naloxone wears off. That’s why hospitals monitor patients for at least 4-6 hours, sometimes longer.

And dosage? If the person weighs over 100 kg, they don’t get more acetylcysteine. The dose is capped at 100 kg. Giving more doesn’t help - and can cause side effects.

Benzodiazepines: The Silent Complication

Many people who overdose on opioids also take benzodiazepines - Xanax, Valium, Klonopin. These are sedatives. They make breathing slower. They’re often prescribed for anxiety or sleep. But together with opioids? Deadly.

Flumazenil is the antidote for benzodiazepines. But here’s the catch: if someone has been taking these drugs daily for weeks or months, flumazenil can trigger seizures. It pulls the drug out of the system too fast. The brain goes into overdrive. So doctors rarely use it. Instead, they support breathing, wait it out, and monitor.

Tramadol is another curveball. It’s not a classic opioid, but it acts like one. It can cause seizures and serotonin syndrome. Naloxone helps - but often not enough. You might need a continuous IV drip of naloxone because tramadol lasts 5-6 hours. One dose won’t cut it.

When Hemodialysis Becomes Necessary

In the worst cases - when acetaminophen levels hit 900 μg/mL or higher, and the person is confused or in acidosis - the liver is beyond saving. That’s when hemodialysis kicks in. It’s a machine that filters the blood, removing toxins. But it’s not simple. Acetylcysteine must keep running during dialysis - at 12.5 mg/kg per hour - because the machine also removes the antidote. You’re fighting two battles at once.

This is rare. But when it happens, survival depends on acting fast. Delaying dialysis by even a few hours can mean the difference between recovery and liver transplant - or death.

What Happens After the Emergency?

Surviving an overdose doesn’t mean you’re done. The body still needs healing. The mind needs help.

Activated charcoal can interfere with other medications - including birth control. If someone takes charcoal, they need to use backup contraception for the next 7 days. It’s not obvious. But it’s critical.

And then there’s the bigger issue: addiction. The World Health Organization says people released from prison face the highest overdose risk - up to 130 times higher in the first four weeks. Why? Their tolerance drops. They go back to using the same dose they used before jail. Their body can’t handle it anymore.

That’s why follow-up care matters. A person who overdoses needs to see a doctor within 72 hours. Not just for liver checks. For mental health. For treatment options like methadone or buprenorphine. Programs that link overdose survivors to long-term care have cut death rates by up to 50%.

Community naloxone programs have saved tens of thousands of lives. In the U.S. alone, over 265,000 kits were distributed in 2021. But distribution alone isn’t enough. Training is. People need to know how to recognize the signs, how to use the nasal spray, and how to stay with someone until help arrives.

Prevention Is the Real Solution

Medications like Vicodin and Percocet are still widely prescribed. Many people don’t realize they’re taking acetaminophen in multiple pills - painkillers, cold medicine, sleep aids. One extra pill a day can push you over the limit.

Doctors are getting better at checking for this. But patients need to ask: “Does this medicine have acetaminophen?” and “How much is too much?” The safe daily limit is 3,000-4,000 mg. That’s less than you think.

And naloxone? It should be as common as an EpiPen. Keep it in your car. Keep it in your bag. If you know someone using opioids - even if they’re in recovery - give them a kit. Teach them how to use it. Teach their friends too.

Multiple drug overdose isn’t a moral failure. It’s a medical failure. We have the tools to stop it. We just need to use them - fast, smart, and together.

Comments

Sue Stone January 24, 2026 at 09:31

Been there. Saw my brother go down with a mix of oxycodone and Xanax. No one knew what to do. Naloxone saved him, but he was out for 20 minutes before EMS showed up. If I hadn’t been there doing breaths? He wouldn’t be here. People need to stop pretending this isn’t happening.

Janet King January 24, 2026 at 14:23

It is critical to understand that acetaminophen toxicity often presents without symptoms for up to 24 hours. Liver enzymes must be monitored serially. Acetylcysteine should be initiated without delay if there is any suspicion of ingestion exceeding 150 mg per kg. Delayed treatment increases mortality risk significantly.

Susannah Green January 25, 2026 at 16:53

So many people don’t realize that Tylenol is acetaminophen… and that cold medicine, sleep aids, even some migraine pills have it too. I’ve seen friends take 3 extra pills ‘just to be sure’… and then wake up in the ER. It’s not a joke. It’s a silent killer. Please check the labels. Please.

Stacy Thomes January 26, 2026 at 00:33

IF YOU KNOW SOMEONE USING OPIODS-GIVE THEM NALOXONE. LIKE, RIGHT NOW. Don’t wait for them to ‘get their life together.’ Don’t wait for them to ‘ask for help.’ They might not get the chance. Keep a kit in your car, your purse, your damn sock drawer. It’s not a death sentence-it’s a second chance.

charley lopez January 27, 2026 at 23:48

The pharmacokinetic interaction between fentanyl and benzodiazepines demonstrates a synergistic suppression of central respiratory drive, which is not adequately addressed by single-agent antidotal therapy. Naloxone’s half-life is substantially shorter than that of many synthetic opioids, necessitating prolonged observation periods beyond standard protocols.

Kerry Evans January 29, 2026 at 05:29

People think this is just about ‘bad choices.’ No. It’s about a broken system. Doctors overprescribe. Pharmacies don’t warn. Insurance won’t cover rehab. And then we act shocked when someone dies. You want to fix this? Stop blaming addicts. Start fixing the pipeline. And yes-I’m talking to you, big pharma.

Kerry Moore January 30, 2026 at 00:53

Thank you for outlining the clinical protocols so clearly. I’m curious-how do hospitals prioritize which antidote to administer first when multiple agents are involved? For example, if naloxone and acetylcysteine are both indicated, is there a standardized sequence, or is it case-dependent based on vitals and lab values?

Andrew Smirnykh January 30, 2026 at 18:04

In my country, we don’t have naloxone available over the counter. People die waiting for a doctor. I wish this kind of knowledge was taught in schools-not just to first responders. Everyone should know how to save a life. Even if it’s just breathing for someone until help comes.

Laura Rice January 31, 2026 at 21:46

My cousin overdosed last year. They gave him naloxone, he woke up, smiled… and then stopped breathing again 90 minutes later. No one told us it could happen twice. Please-tell people this. Tell their families. Tell their friends. This isn’t just medical info. It’s survival info.