When you take a pill for high blood pressure, you expect every tablet to be exactly the same. That’s because small-molecule drugs are made in a lab using chemical reactions - the same ingredients, same process, same result. But when you’re on a biologic - like a drug for rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or cancer - what’s in your syringe isn’t a single molecule. It’s a family of millions of slightly different versions of the same protein. And that’s where lot-to-lot variability comes in.

What Exactly Is Lot-to-Lot Variability?

Lot-to-lot variability means that each batch, or "lot," of a biologic drug made by the same company can have tiny differences from the one before it. These aren’t mistakes. They’re natural. Biologics aren’t manufactured like aspirin. They’re grown inside living cells - usually Chinese hamster ovary cells or yeast. Those cells are alive. They change. They respond to temperature, nutrients, pH, even the air in the room. And when they make a protein - say, a monoclonal antibody - they don’t always make it perfectly the same way every time.The differences show up in things like glycosylation - the sugar molecules stuck onto the protein. Or how certain amino acids are modified. These aren’t random errors. They’re normal biological noise. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says it clearly: "A lot of a reference product and biosimilar can contain millions of slightly different versions of the same protein or antibody."

Think of it like baking sourdough bread. Two loaves from the same baker, using the same recipe, can still taste a little different. One might be tangier. Another might have a slightly different crust. That doesn’t mean the baker is inconsistent. It means the ingredients - the wild yeast, the flour, the humidity - are alive and changing. Biologics work the same way.

Biosimilars Aren’t Generics. Here’s Why.

You’ve probably heard that biosimilars are "generic versions" of expensive biologics. That’s misleading. Generics for pills like metformin or lisinopril are exact copies. Their chemical structure is identical. A generic version of a small-molecule drug must prove it’s the same molecule, in the same amount, absorbed the same way.Biosimilars are different. They’re highly similar, but not identical. Why? Because you can’t copy a living system like you copy a chemical formula. The FDA says it plainly: "Biosimilars Are Not Generics."

For a biosimilar to get approved, the manufacturer must show it’s "highly similar" to the original biologic - the reference product - with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. That means testing thousands of samples. Looking at protein shape, sugar patterns, how it binds to targets, how it behaves in the body. It’s not just about what’s in the vial. It’s about what the drug does in a person.

And here’s the key: the biosimilar must match the reference product’s range of variability. If the original drug’s lots vary in glycosylation by 5%, the biosimilar’s lots must fall within that same 5%. It doesn’t have to be identical to one lot. It has to behave like the whole family of lots from the original.

How Do Regulators Handle This?

The FDA doesn’t treat lot-to-lot variability as a flaw. They treat it as a fact of life. Their entire approval process for biosimilars - called the 351(k) pathway - is built around it. Manufacturers must submit data showing they can control and monitor variation. They need to prove their manufacturing process is consistent, even if the final product isn’t perfectly uniform.The FDA looks at three things: analytical studies (how similar the molecules are), functional studies (how the protein acts in a test tube), and clinical studies (how patients respond). For a biosimilar to be labeled "interchangeable" - meaning a pharmacist can swap it for the original without asking the doctor - they need even more. They must prove that switching back and forth between the reference product and the biosimilar doesn’t increase risk or reduce effectiveness. That means running studies where patients alternate between the two drugs over months.

As of May 2024, the FDA has approved 53 biosimilars in the U.S. Twelve of those have interchangeable status. That number is growing fast. By 2026, about 70% of new biosimilar applications are expected to include interchangeability data - up from 45% in 2023.

What Does This Mean for Labs and Testing?

This isn’t just a drug manufacturing issue. It hits labs too. Many lab tests use biologics as reagents - the chemicals that detect things like HbA1c (a diabetes marker) or thyroid hormones. When a lab switches to a new lot of reagent, they have to check if the results change.Here’s the problem: QC (quality control) samples don’t always behave like real patient samples. A new reagent lot might show perfect QC numbers but still shift patient results by 0.5%. That might sound small. But in diabetes care, a 0.5% change in HbA1c could mean the difference between "well-controlled" and "poorly controlled." That’s why 78% of lab directors say lot-to-lot variation is a significant challenge.

Labs use statistical methods to catch this. They test 20 or more patient samples with the new lot and compare them to the old one. They need enough samples to have an 80-95% chance of spotting a real difference. If the results drift outside a predefined limit, they can’t use the new lot. That’s time-consuming. Smaller labs spend 15-20% of their tech time just verifying reagent lots.

Why This Matters for Patients

You might wonder: if the differences are so tiny, why should I care? The answer is trust.If you’ve been on a biologic for years - say, adalimumab for psoriasis - and your doctor switches you to a biosimilar, you need to know it won’t suddenly stop working or cause new side effects. The science says it won’t. But patients worry. And rightly so. When a test result changes unexpectedly, or a drug seems less effective, it’s natural to blame the new version.

That’s why interchangeability matters. It’s not just a regulatory label. It’s a promise. It means the biosimilar has been tested not just once, but repeatedly - with patients switching back and forth - and no safety or effectiveness issues were found. That’s the gold standard.

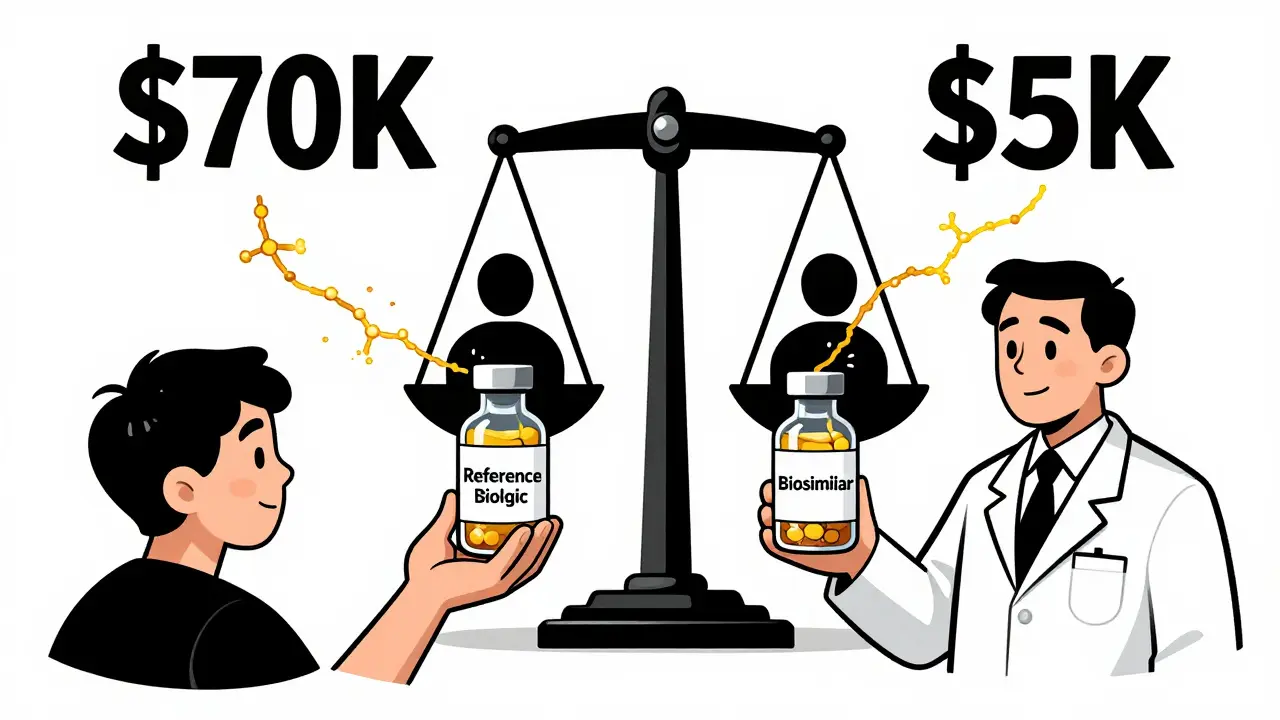

And the numbers show it works. Biosimilars now make up about 32% of all biologic prescriptions in the U.S. by volume. Patients are getting the same care at a fraction of the cost. The original biologic for adalimumab (Humira) cost over $70,000 a year. Biosimilars now cost under $5,000.

The Future: More Complexity, More Control

The next wave of biologics is even more complex: antibody-drug conjugates, cell therapies, gene therapies. These aren’t just proteins. They’re living cells engineered to fight disease. Their variability? Even harder to control.But technology is catching up. New tools like high-resolution mass spectrometry and AI-powered analytics can now detect differences in proteins that were invisible a decade ago. Manufacturers are using machine learning to predict how small changes in their process will affect the final product. The goal isn’t to eliminate variability - that’s impossible. It’s to understand it, predict it, and keep it within safe, effective limits.

What’s clear is this: lot-to-lot variability isn’t a bug in the system. It’s a feature of biology. And the regulatory system, labs, and manufacturers are learning how to live with it - and even use it to make better, more affordable medicines.

What You Should Know

- Biologics naturally vary between lots - it’s not a defect, it’s normal. - Biosimilars aren’t generics. They’re highly similar, not identical, and must match the reference product’s variability range. - Interchangeable biosimilars have passed extra tests to prove switching won’t hurt you. - Labs verify reagent lots using patient samples, not just control samples, because patient results don’t always mirror QC. - Cost savings are real. Biosimilars cut biologic drug prices by 80-90% in many cases. - More are coming. By 2028, the global biosimilars market is expected to hit $35.8 billion.If you’re on a biologic, ask your doctor: "Is this a biosimilar? Is it interchangeable?" You have a right to know. And if you’re switching, monitor how you feel. Most people won’t notice a difference. But if something changes - fatigue, flare-ups, side effects - tell your provider. Your experience matters.

Comments

Jane Wei December 17, 2025 at 06:32

Wow, this is actually way more interesting than I expected. I thought biologics were just fancy pills, but now I get it-they’re like living art. 🤯

amanda s December 17, 2025 at 18:02

This is why America leads in biotech-no other country has the nerve to let biology be messy and still call it medicine. We don’t sanitize science, we master it.

Nishant Desae December 18, 2025 at 21:28

As someone from India where access to these drugs is still a luxury, I find this so important. The cost difference isn’t just numbers-it’s life or death for so many families. I’ve seen patients cry because they couldn’t afford Humira, and then smile when they got the biosimilar. It’s not perfect, but it’s hope. And hope matters more than perfect chemistry.

Peter Ronai December 20, 2025 at 11:51

Oh please. You’re telling me we’re supposed to trust a drug made by ‘living cells’ that ‘can’t be perfectly replicated’? That’s not science-that’s witchcraft with a FDA stamp. If it’s not identical, it’s not medicine. It’s a gamble with your immune system.

Martin Spedding December 20, 2025 at 22:45

Biologics? More like bioweapons with a price tag.

Salome Perez December 21, 2025 at 21:29

Thank you for this thoughtful breakdown-it’s rare to see such clarity on a topic that’s so often clouded by hype and fear. The sourdough analogy? Brilliant. It’s not about perfection; it’s about consistency within natural bounds. And yes, labs are scrambling to keep up. I’ve seen a colleague spend three days validating a single reagent lot because the HbA1c results drifted just 0.4%. That’s not inefficiency-that’s responsibility.

What’s truly inspiring is how regulators are adapting. Instead of demanding impossible perfection, they’re asking: ‘Does it work safely for people?’ That’s patient-centered science. And the fact that 12 biosimilars are now interchangeable? That’s not just regulatory progress-it’s moral progress.

To those worried about switching: I get it. Change is scary. But the data is overwhelming. Millions of doses administered. No meaningful safety signals. The real risk isn’t the biosimilar-it’s the fear that keeps people from affordable care.

And to the labs? You’re the unsung heroes. Your patience, your statistical rigor, your refusal to accept QC as gospel-that’s what keeps patients safe. Keep doing what you do.

Let’s not confuse biological reality with medical failure. This isn’t broken. It’s evolving. And we’re learning to dance with it.

Jessica Salgado December 22, 2025 at 02:01

Wait-so if a biosimilar has to match the variability range of the original, that means the original isn’t even perfectly consistent? So we’re basically giving people medicine that’s always slightly different… and calling it safe? I’m not sure I’m okay with that.

Chris Van Horn December 22, 2025 at 23:35

One must question the epistemological foundations of pharmaceutical regulation when the very notion of identity is abandoned in favor of statistical approximation. The FDA’s embrace of biological stochasticity as a ‘feature’-not a bug-is not merely regulatory leniency; it is a surrender to ontological chaos. How can a physician prescribe with confidence when the molecular substrate of therapeutic efficacy is, by design, non-reproducible? This is not medicine. This is alchemy with a compliance checklist.

And to suggest that ‘millions of slightly different versions’ are acceptable is to redefine the very concept of a drug. A pill is a pill. A molecule is a molecule. A biologic is… what? A cloud? A mood? A whisper of protein? The implications for pharmacovigilance are terrifying. How do you trace an adverse reaction when the offending agent is never the same twice? We are building a house on sand, and calling it a foundation.

Interchangeability? A dangerous illusion. You cannot swap a variable for a variable and expect consistency. The clinical trials are cherry-picked, the patient populations too narrow, the follow-up too brief. What of the elderly? The immunocompromised? The polypharmacy patients? They are not in the trials. They are the real world. And the real world does not tolerate ambiguity.

And let us not forget the economic coercion: ‘It’s cheaper!’-as if cost should ever override molecular fidelity. We are not buying bread. We are not brewing tea. We are inserting a biological agent into the sacred architecture of human physiology. Precision is not optional. It is sacred.

It is no wonder that European regulators remain more cautious. They understand: when biology becomes a variable, medicine becomes a lottery. And no patient should be forced to play.

Patrick A. Ck. Trip December 23, 2025 at 21:35

I appreciate the nuance here. It’s easy to fear what we don’t understand. But biology has always been messy. Even our own bodies aren’t perfectly consistent from day to day. The fact that we can harness that chaos and turn it into life-saving therapy is remarkable. We’re not just making drugs-we’re working with life itself. That’s humbling.

And yes, labs are doing the heavy lifting. I’ve seen techs spend hours validating reagents because they know a 0.5% shift could mean a diabetic patient gets misclassified. That’s not bureaucracy. That’s care.

Let’s not let perfectionism stop progress. The cost savings alone mean thousands can now access treatment. That’s not a bug. That’s a breakthrough.

Raven C December 24, 2025 at 14:17

How… quaint. You speak of ‘sourdough’ as if it were a valid analogy for human physiology. One might as well compare a symphony to a garage band and say ‘they’re both music.’ The distinction between ‘highly similar’ and ‘identical’ is not academic-it is existential. When a patient’s immune system reacts unpredictably, who bears the blame? The doctor? The pharmacist? The patient? Or the FDA, for permitting this molecular roulette?

And yet, you call this ‘progress.’ I call it negligence dressed in data.

Jonathan Morris December 24, 2025 at 23:35

Let’s be real: this whole ‘lot variability’ thing is a cover-up. Big Pharma doesn’t want to admit they can’t control their own products. So they rebrand chaos as ‘biological reality.’ Meanwhile, the same companies are raking in billions from the original biologics-and now they’re selling the ‘biosimilar’ version at 90% off, but it’s the same factory, same cells, same people. They just slapped a new label on it. And now they’re telling us it’s ‘interchangeable’? Please. The FDA is a puppet. The real question: who’s pulling the strings? And why are we letting them play god with our immune systems?

Kent Peterson December 25, 2025 at 09:25

Let’s cut through the fluff: if a drug’s molecular structure isn’t identical across batches, it’s not a drug-it’s a placebo with a patent. The FDA’s ‘highly similar’ standard is a legal loophole masquerading as science. And the fact that labs are spending 20% of their time verifying reagent lots? That’s not diligence-it’s damage control. Why are we tolerating this? Because it’s cheaper? That’s not healthcare-it’s corporate risk management disguised as innovation.

And don’t give me that ‘biological noise’ nonsense. Noise is static. This is a manufactured product. If you can’t control it, you shouldn’t be selling it. Period.

Interchangeable? Ha. That’s not a regulatory achievement-it’s a public relations stunt. The clinical data is cherry-picked. The long-term effects? Unknown. The patients? Uninformed. And the cost savings? A distraction from the fact that we’re normalizing medical uncertainty.

And for the love of all that’s rational: stop comparing biologics to sourdough. Bread doesn’t have immune receptors. People do.

Naomi Lopez December 26, 2025 at 14:33

Ugh, I hate when people treat biologics like they’re magic. They’re just proteins. Sure, they’re complicated, but so what? We’ve been doing this for decades. The ‘variability’ is just noise. If your body reacts to one batch and not another, maybe you’re just sensitive. Or maybe you need to stop being so dramatic.

Also, why are we even talking about this? It’s not like patients are dying from biosimilars. We’re just saving billions. Let’s move on.

Michael Whitaker December 27, 2025 at 05:14

Actually, I think the analogy to sourdough is dangerously reductive. Sourdough doesn’t have a CD20 receptor. It doesn’t trigger cytokine storms. You can’t swap one loaf for another and expect the same immune response. The FDA’s approach is not ‘adaptive’-it’s negligent. And the fact that labs are now forced to validate reagents against patient samples instead of QC controls? That’s not innovation. That’s a system collapsing under its own complexity.

And yet, we’re told to trust it. Because ‘cost savings.’

I’ll believe it when I see a double-blind, 10-year longitudinal study on switching between reference and biosimilar in real-world, multi-morbid populations. Until then, I remain… skeptical.

Virginia Seitz December 28, 2025 at 02:45

So basically… biologics are like handmade sweaters? 🧶 Each one’s a little different, but they all keep you warm? That’s kinda beautiful, actually. ❤️

Patrick A. Ck. Trip December 28, 2025 at 05:29

Virginia, your sweater analogy is actually the most accurate thing I’ve read all week. We’re not building machines-we’re working with biology. And sometimes, the ‘imperfections’ are what make it work. The body adapts. The immune system learns. Maybe the variability isn’t a flaw… maybe it’s part of the design.