Most people think flushing medicine down the toilet is bad for the environment - and they’re right. But there’s a small, specific list of medications the FDA says you should flush - and only if you have no other choice.

This isn’t about convenience. It’s about saving lives. Some pills, patches, or liquids are so dangerous that if a child, pet, or stranger finds them in the trash, one dose can kill. The FDA created the Flush List to give people a last-resort option when take-back programs aren’t available. It’s not a green solution. It’s a safety net.

Why Flushing Is Usually a Bad Idea - But Not Always

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) doesn’t want you flushing meds. Pharmaceuticals in water systems harm fish, frogs, and ecosystems. That’s why most drugs should go to a take-back program, a pharmacy drop box, or be mixed with coffee grounds or cat litter and thrown in the trash.

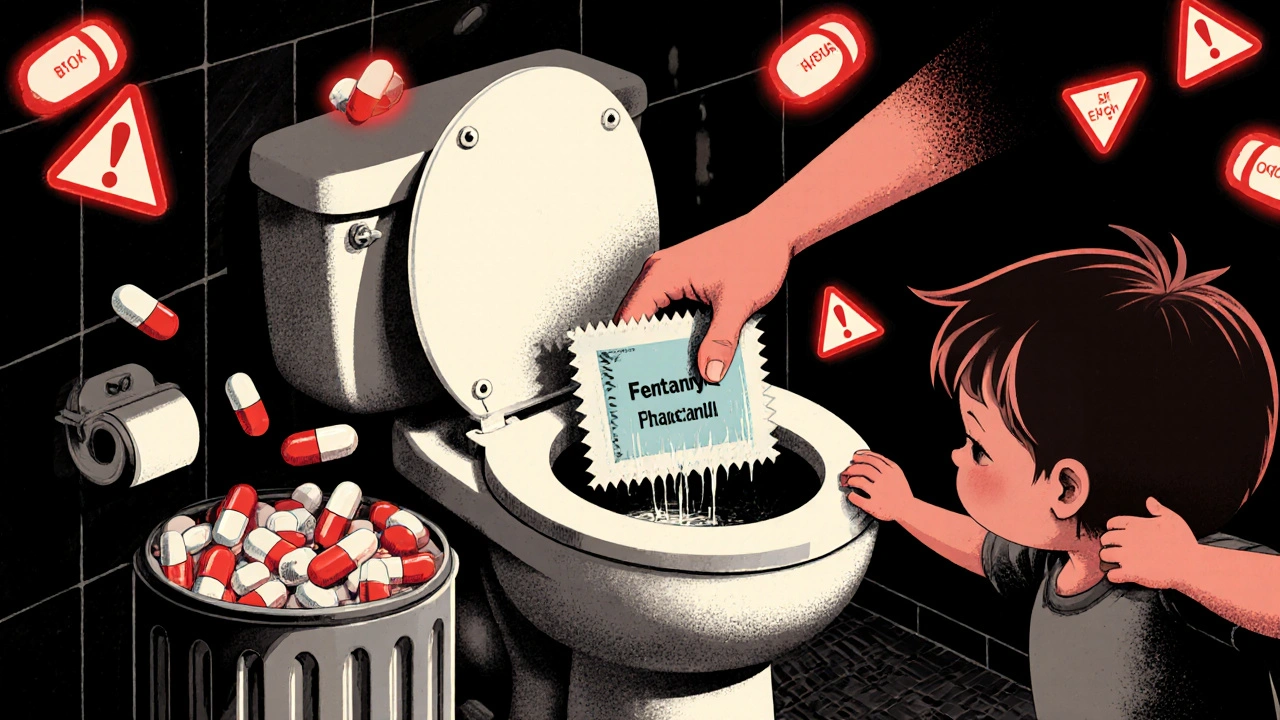

But here’s the catch: some medications are too dangerous to risk in the trash. If a child finds a fentanyl patch in the garbage and sticks it to their skin, they could die within minutes. A single pill of methadone or oxymorphone can be fatal to someone who’s never taken opioids before. The FDA’s job isn’t to protect waterways - it’s to protect people from immediate, life-threatening exposure.

That’s why the Flush List exists. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a public health rule written in response to real deaths. Between 2010 and 2022, the FDA documented 217 cases of accidental fentanyl exposure in children, with 9 of them fatal. Most of those cases came from improperly discarded patches.

The FDA Flush List: What Medications Can You Flush?

The list is short - and it’s updated. As of April 2024, only these active ingredients are approved for flushing when take-back options aren’t available:

- Buprenorphine - found in BELBUCA, BUAVAIL, BUTRANS, SUBOXONE, SUBUTEX, ZUBSOLV

- Fentanyl - in ABSTRAL, ACTIQ, DURAGESIC patches, FENTORA, ONSOLIS

- Hydromorphone - specifically EXALGO extended-release tablets

- Meperidine - brand name DEMEROL

- Methadone - DOLOPHINE, METHADOSE

- Morphine - ARYMO ER, AVINZA, EMBEDA, KADIAN, MORPHABOND ER, MS CONTIN, ORAMPH SR

- Oxymorphone - OPANA, OPANA ER

- Tapentadol - NUCYNTA, NUCYNTA ER

- Sodium oxybate - XYREM, XYWAV

- Diazepam rectal gel - DIASTAT, DIASTAT ACUDIAL

- Methylphenidate transdermal system - DAYTRANA

That’s it. Only these 15 active ingredients. If your medicine isn’t on this list, don’t flush it. Even if it’s old, expired, or you don’t need it anymore. Flushing anything else is against FDA guidance.

For patches - especially fentanyl - fold them in half with the sticky sides together before flushing. This keeps the drug from leaking out and reduces environmental exposure. Don’t just toss the patch in the toilet. Fold it. Then flush.

When Flushing Is the Only Option

The FDA is clear: take-back programs are always the first choice.

There are over 12,000 authorized collection sites across the U.S., including pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations. The DEA runs National Take Back Days twice a year - in April and October - where you can drop off meds for free. You can also search for year-round drop-off locations on the DEA’s website.

But what if you live in a rural area? What if the nearest drop-off is 50 miles away? What if it’s 8 p.m. on a Tuesday and you just found your teenager’s old painkiller bottle?

That’s when flushing becomes the right move.

A 2023 survey found that 78% of patients told by pharmacists about safe disposal didn’t know where to take their meds. In some rural counties, there’s one take-back site for every 50,000 people. For many families, flushing is the only way to prevent a tragedy.

Don’t wait. If you have any of the medications on the Flush List and you can’t get to a drop-off within a day or two - flush it. Don’t store it. Don’t hide it. Don’t hope you’ll remember later. Do it now.

What You Should Never Flush

Here’s what’s not on the list - and why you should never flush it:

- Antibiotics (like amoxicillin or azithromycin)

- High blood pressure pills (like lisinopril or amlodipine)

- Antidepressants (like sertraline or fluoxetine)

- Cholesterol meds (like atorvastatin)

- Insulin

- Vitamins or supplements

- Over-the-counter painkillers (ibuprofen, acetaminophen)

These aren’t safe to flush. They don’t pose the same immediate overdose risk. But they still pollute water. For these, mix them with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal them in a plastic bag, and throw them in the trash. Remove labels first to protect your privacy.

And don’t be fooled by old advice. A decade ago, many people were told to flush everything. That’s outdated. The FDA has tightened the list over time. In 2021, they removed 11 medications because newer, safer formulations made flushing unnecessary.

How to Dispose of Medications the Right Way

Follow this simple 3-step process:

- Check if your medication is on the FDA Flush List. Look at the active ingredient on the bottle. Compare it to the list above. If it’s there, you might flush - but only if step 2 isn’t possible.

- Find a take-back location. Visit the DEA’s website or call your local pharmacy. Many Walgreens, CVS, and Walmart locations have drop boxes. Some police stations do too. If you’re in a city, chances are there’s one nearby. If you’re in the country, check if your county runs a collection event.

- Only flush if you absolutely can’t do either of the above. Fold patches. Flush pills whole. Don’t crush them. Don’t dissolve them. Just flush. Then remove your name from the bottle before tossing it in the trash.

That’s it. No guessing. No exceptions.

What Happens If You Flush the Wrong Medicine?

If you flush something not on the list, you’re not breaking the law - but you’re ignoring public health guidance. You’re adding chemicals to water systems that could harm wildlife and potentially enter drinking water supplies.

Scientists from the USGS found traces of 8 Flush List medications in 23% of streams they tested. But here’s the key: those levels were far below what’s needed to affect humans. The real danger isn’t the water - it’s the trash can.

That’s why the FDA’s logic is so clear: if a pill can kill a child in minutes, the environmental risk of flushing it is worth it. But if a pill won’t kill someone from one dose? Then the environment comes first.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is reviewing the list again. In 2023, there were 17 reported cases of accidental buprenorphine exposure in children - all from patches thrown in the trash. That’s why the agency is considering adding new transdermal forms to the list.

At the same time, they’re looking at removing some existing ones. Three medications may be taken off the list by 2025 because newer versions have abuse-deterrent features - like pills that turn to gel when crushed, making them harder to misuse.

Pharmaceutical companies are also starting to print disposal instructions right on the label. In 2023, 87% of controlled substance packaging included clear disposal steps. That’s a big improvement from 10 years ago.

Final Reminder: Safety Over Everything

Flushing medicine isn’t ideal. But saving a life is more important than keeping water clean. If you have a medication on the FDA Flush List and you can’t get it to a take-back site - flush it. Don’t wait. Don’t hesitate.

And if you don’t have one of those meds? Don’t flush. Mix it with something gross, seal it up, and toss it. Then, next time you get a prescription, ask your pharmacist: "Where can I drop this off when I’m done?"

One small habit - checking the label, asking questions, knowing the list - can prevent a tragedy.

Comments

Henrik Stacke November 23, 2025 at 09:56

Remarkably nuanced piece-this isn't just about disposal protocols; it's a microcosm of public health triage. The FDA’s calculus-prioritizing acute human risk over ecological contamination-is ethically defensible, if not elegantly so. The 217 documented pediatric exposures since 2010, nine fatal, underscore a grim reality: environmental purity cannot be the default when the alternative is a child’s death in under ten minutes. We must stop romanticizing green ideals at the cost of lived safety.

Dalton Adams November 23, 2025 at 16:22

Let’s be real-this list is a joke. Fentanyl patches? Sure. But why is oxymorphone on there but not hydromorphone ER? And what about the 37 other opioids that are just as lethal? The FDA’s list is a political compromise, not science. They removed 11 meds in 2021 because pharma lobbied for abuse-deterrent formulations-so now we’re supposed to trust that the new ones are safe? Please. The real issue is that no one has a nationwide take-back infrastructure. This isn’t a flush list-it’s a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

Also, why does diazepam rectal gel need flushing? That’s a seizure rescue med-most families keep it in the car. You think a kid’s gonna find it in the glovebox and flush it? No. They’ll find it in the bathroom cabinet. So flush it? Or lock it up? The answer is both. But the FDA won’t say that.

Kane Ren November 24, 2025 at 03:10

God, I’m so glad someone finally laid this out clearly. I used to toss all my meds in the trash-until my cousin’s kid got into his dad’s old OxyContin. He’s fine now, but we almost lost him. That’s when I started checking the label every time. Now I keep a little bin in the cabinet for anything on the flush list. Fold the patch, flush it, done. No guilt. No hesitation. This isn’t about being eco-friendly-it’s about being a responsible adult. Thank you for the clarity.

Javier Rain November 24, 2025 at 18:45

Yes. This. I work in rural EMS. We’ve responded to three opioid overdoses in the last year from kids finding pills in trash cans. One was a 7-year-old who got into his grandfather’s methadone bottle. He’s in rehab now. We don’t have a single take-back drop box within 40 miles. Flushing isn’t ideal-it’s the only thing that stops a funeral. Stop shaming people for doing the right thing when the system fails them.

Manjistha Roy November 26, 2025 at 04:05

Thank you for this comprehensive breakdown. I am from India, where medication disposal is rarely discussed, and I have seen neighbors flush everything-antibiotics, insulin, even multivitamins. This list is a revelation. The distinction between immediate toxicity and chronic environmental impact is critical. I will share this with my community. We must educate. We must act. No more guesswork. No more tradition. Only facts.

Jennifer Skolney November 26, 2025 at 21:33

I just flushed my mom’s last fentanyl patch last week. She passed last month. We didn’t know what to do with it. I cried while I folded it. I didn’t want to, but I did. Thank you for saying it’s okay to do that. I felt so guilty before. Now I know I did the right thing.

JD Mette November 28, 2025 at 00:27

Interesting. I didn’t know about the fold-before-flush step. I always just dropped them in. I’ll do that from now on. Also, I didn’t realize the list had been trimmed. I thought it was longer. Good to know the guidelines are evolving.

Laurie Sala November 28, 2025 at 01:34

Why is no one talking about how this is just another way the government makes you feel guilty for surviving? You’re supposed to feel bad for flushing? You’re supposed to drive 50 miles to drop off a pill that could kill your kid? And if you don’t? You’re a bad parent. A bad citizen. A bad human. The system is broken, and now we’re the ones who have to carry the emotional weight of it. I’m not sorry I flushed it. I’m sorry the system made me feel like I had to.

Charmaine Barcelon November 28, 2025 at 14:56

Ugh. This is why people are dumb. You flush ANYTHING that’s not on the list? You’re a menace. Do you even know what’s in your water? You think your tap water is clean? It’s full of antidepressants and birth control pills from people like you. You’re poisoning the planet. And now you’re going to tell me it’s okay because your kid might find a pill? What about the frogs? The fish? The future? You’re selfish.

Olanrewaju Jeph November 30, 2025 at 00:40

This is a well-structured, evidence-based guide. The distinction between acute toxicity and chronic environmental contamination is scientifically sound. The inclusion of specific active ingredients, rather than brand names, enhances utility. The directive to fold transdermal patches prior to disposal is a critical procedural detail often overlooked. The reference to DEA collection sites is commendable, and the data on rural access gaps underscores systemic inequity in public health infrastructure. Well done.

Kezia Katherine Lewis December 1, 2025 at 03:12

As a clinical pharmacist, I’ve counseled hundreds of patients on this exact issue. The most common misconception is that ‘expired’ means ‘safe to flush.’ It doesn’t. The second is that ‘if it’s not on the list, I can mix it with kitty litter and call it good.’ You can-but only if you’re certain it’s not on the flush list. The real tragedy isn’t the flushing-it’s the ignorance. I’ve seen patients keep opioids in their nightstand for years because they didn’t know what to do. This guide should be printed on every prescription bottle.

Lisa Detanna December 2, 2025 at 20:04

Thank you for not framing this as a moral dilemma. It’s a logistical one. The FDA isn’t asking us to choose between water and life-they’re saying: ‘If you can’t get it to a safe place, here’s the least-bad option.’ That’s not hypocrisy. That’s pragmatism. And we need more of that in public health messaging. No shaming. No guilt. Just clear steps. This is how you change behavior.

Karla Morales December 4, 2025 at 13:41

📊 DATA POINT: 78% of patients didn’t know where to dispose of meds. 📊 217 pediatric exposures since 2010. 📊 9 deaths. 📊 12,000+ take-back sites exist. 📊 Only 14% of Americans use them. 📊 87% of controlled substance packaging now includes disposal instructions. 📊 11 meds were removed from the flush list in 2021. 📊 Fentanyl patches are the #1 source of accidental exposure. 📊 You’re not saving the planet by flushing. But you might be saving a life. 📊 So flush. Fold. Don’t hesitate. 📊 This isn’t activism. It’s harm reduction. 📊 And you’re either part of the solution or part of the problem.

Demi-Louise Brown December 6, 2025 at 08:45

Clear, factual, and necessary. The emphasis on take-back programs as the primary solution is correct. The exceptions are justified. The folding instruction is critical. The removal of outdated items from the list shows adaptability. This is how public health communication should be done: precise, calm, and authoritative. No drama. No fearmongering. Just facts. Well done.

Matthew Mahar December 6, 2025 at 20:16

wait so i can flush my exs oxycontin? i thought that was bad?? i mean i know its on the list but like… i dont wanna be the guy who poisons the river?? but also i dont wanna my niece find it?? idk man… i think i’ll just bury it in the backyard… 😅